Cool subject, right? I'm not sure I'll do it justice, but this does relate to some different thoughts I've been considering for awhile. After sketching out where this is going I'll move onto awhile back on when these lines of thought first occurred to me, related to writing a journal when I was much younger, then on to more of what I'm trying to get at.

Narrative themes in everyday life

Of course a lot of aspects of our lives rely on ideas sorting into narrative themes, story lines. Running threads include a career (or not), relationships, family life, hobbies that develop, etc. It's really not something that could be good or bad, we would just need to arrange ideas in that way to make sense of what we experience. At the same time a lot of what we go through is really random, in terms of individual events, even if the background context remains tied those themes. If I run late or not to work that's not part of daily story line, aside from being late coloring some later events; it's not like the fickle hand of fate has lateness in store for me that day. But then astrology sort of includes the idea that such patterns are built into our lives, doesn't it, that shorter and longer term patterns are coming from mysterious external sources, not just related to how many people happen to be using the same roads just then. My computer freezes up due to a Mercury retrograde, and such.

The idea here is to go into how immediate experience is related to this type of interpretation, not really about astrology, but the extent to which daily events need to be woven into a running thread, a story line, or the extent to which that's just habit. Of course patterns like waking, showering, breakfast, commuting to work, etc. are recurring in the same order, so that's not what I mean. I'm talking about overlaying a storyline-framed interpretation to immediate experience, or not doing that. It will make more sense related to an example, about writing a journal, and in relation to some ideas from Buddhism about immediate experience, and the role interpretation plays in that.

Journal writing experience, and Buddhism related to narrative themes

In my 20s I practiced writing a journal, essentially like a diary, just to practice writing, and to keep track of things that happened. It should make for an interesting read someday, whenever I get back to it, because it was an interesting time in my life. I was a ski-bum then, in Colorado (in the Vail Valley, if that matters). An engineering career went badly prior to that, nearly out of the gate (I'm an industrial engineer, by training), so I decided to take a year off and join a friend skiing and working instead, which ran long. Lots of things didn't go according to that original plan. For example, I took up snowboarding instead of skiing, back in the early 90s. That was also really back when snowboarding first took off, and when they first developed relatively modern boards.

But I digress; back to the journal idea. It was a nice way to explore writing, but I noticed one odd side-effect: I would tend to see events as I would write them, to constantly arrange them into narrative themes. As I mentioned normal life experience itself naturally falls into such patterns, to some extent, but it's only necessary for that to happen related to the larger scope, about taking a next job, or pursuing a relationship. If you just go for a hike or get in a long line at the grocery store there's no need to work on how those would be written up, you can just live it out, and daydream, or think about politics. Or I guess now it would be more normal to watch a Facebook feed, or a messenger app, but this was in the 90s.

It's interesting how one might interpret that issue of narration or framing experience mentally in different ways related to Buddhism though, which I also became interested in during that time. It's not simple how the practice of interpreting individual events and experiences in terms of running themes relates to that. Without one clear read I'll talk around some of my own impressions.

Zen Buddhism would be a natural place to start, wouldn't it? That's the school or sub-context within Buddhism that focuses the most on draining immediate experience of interpretation, all about just simply being in the moment, and not reading into that. Ideally that voice in your head just shuts up. There is plenty in original Buddhism that supports that as a valid theme and goal, but Buddhism is really a broad subject, not reducing to one simple core as much as people would tend to express that it does. Thai Buddhism, practiced where I live now, in Bangkok, has relatively nothing to do with all that. Zen was influenced a lot by Taoism, really a development from both schools of thought, by way of a branch of Chinese Buddhism, Chan.

I won't be able to do Chan Buddhism or Zen justice, and this post isn't about that anyway. You could read up more on it starting in Wikipedia, a natural starting point for most subjects. Or in any number of sources Google would be happy to suggest, like this one, a Hong Kong university reference. Here's a bit of what they say about Chan Buddhism (which later essentially became Zen, when the same school and ideas transferred to Japan):

Chan Buddhism can be viewed as pushing the implicit logic of Buddhism to reject the original goal of Buddhism--the quest for Nirvana. Chan is Buddhist atheism. The gradual development of this perspective, however, is a complex one in China and is made even more challenging by a pedagogical practice among Chan masters—"never tell to plainly." Each person should come to her own realization.

All that might be up for debate, open to interpretation. But it seems clear enough the general idea is to limit the role of analytical mediation of direct experience, or at least that seems clear to me, but maybe it's not. Of course this passage is about other things, the relation to religion and method of transmission.

What about "original Buddhism"? Again, this could only be my own take, and I wouldn't be able to justify it by lots of citations, original teachings and related supporting references. I could, if I were into such things, and I've read a frightful amount of core texts and interpretations in the past, but I'm not into it now. This blog is just a place for discussing ideas.

I should probably mention the absolute basics about those branches; "original Buddhism" would be a reference for Theravada Buddhism, the first main branch, which Thai Buddhism is a part of. It was also referred to as Hinayana, which per my understanding was later rejected as a reasonable label since Hinayana refers to "lesser vehicle," a comparison to the Mahayana approach (which means large or great vehicle), related to teaching methods and approach. That size reference isn't obviously negative (more on that in Wikipedia's explanation), but per my understanding Theravada is more typically used now anyway. There is more on all this in any number of source, like this one, which Google could suggest. Vajrayana (diamond or thunderbolt vehicle) relates to later yet teachings, like Tibetan Buddhism, crazy stuff related to magic and sex-oriented practices, surely including some mainstream ideas and approaches as well.

As I take it there is a lot less emphasis on how immediate experience is experienced but essentially the same context applies. Self--or ego, maybe, but that's from a different model--is rejected, and that rejection of self covers a few different levels. The main idea has nothing to do with rejecting story lines in everyday experience, more about immediate interpretation related to desire, and most likely specific forms of it. The short-short version is that even relatively subconscious desires underlie a lot of experience in a negative way, framing normal experience in terms of whatever it happens to lack. Sounds like the typical goal of most marketing, doesn't it? There is a tie-in there.

The general idea in Buddhism--as I take it--is that no matter what we have (own, or experience) we experience desire and lack. Even if we get the things we want most, money, possessions, physical gratification in different forms, whatever it is, then we tend to want more of whatever it is, or else experience a desire to retain it that colors the experience more negatively. All of this ties to self, of course, kind of the central running theme in Buddhism. Self-image also colors immediate experience, not necessarily in only negative ways, but when it relates to a lot of desire it can be negative. It doesn't have to be a conventional form of desire related to self-image, that I'd like to be taller, or about a woman trying to get her make-up just right, it could relate to underlying themes, anxiety over how one is coming across, and so on.

It all sounds more negative than it really is. The Buddha's message wasn't that life is horrible, all about suffering, and only sitting in a cave until experiencing some radical transition can offset that, although that does summarize one take on it. He was saying that we tend to make things worse than they are, and that with the right perspective we could bypass most of that, or potentially even all of it.

At the risk of losing the running point I'll venture a crazy, radical extension of these ideas: it's at least possible that physical discomfort isn't as unpleasant as our aversion to it. Just food for thought; it's not hard to get purchase on the ideas back within the realm of common sense. Anxiety in general could be caused by self-image issues, as I mentioned, or fear of what might potentially happen in the near future or future. Both of those are cases of going outside immediate experience to "suffer" related to something that's not actually happening, in a sense. The same can be true of the past, that regret or a sense of loss can be a self-imposed burden based on carrying the weight of a problem that isn't really present.

Clear enough, isn't it? Expectations or shifts in assumptions can color immediate experience negatively. We might add these to what is really going on. Shutting down analytical forms of cognition in general, one way to take the Zen ideas, is not such a simple prospect. Some of those play vital roles; if I'm driving I'd better pay attention to what may happen in the immediate future, especially in Bangkok traffic, with motorcycles and tuk-tuks buzzing around. Self-image is not necessarily something to just toss out either, or other types of image concerns, at work or in social circumstances. Making sense of how all that really might apply is sort of the tricky part.

This might be a good place for me to drift away from a personal interpretation of Buddhism, though, and to get back to what effect I think those narrative themes might be having.

Narrative themes in writing and life experience

I do more with writing a blog about tea these days. My posts are typically reviews, with research, and lots of rambling on about tangents related to tea, little enough about narrative themes, about telling stories. But one of my favorite other tea blogs is all about that, Steep Stories, as the author describes:

This isn’t a tea review blog. There are far better people out there who do that sort of thing. I’m in it for the stories, and I’m happy to share them with all of you.

It would take a lot of circling back to make that relate to Buddhism, wouldn't it? It's not about that; the general point here is that sometimes interesting ideas are a lot more interesting if framed within the context of a story. If you drink a tea and it's really nice that is nice for you, maybe not so great to hear about. But if there is a background story on who made it and why they made that particular version then reading about that tea can take on a much greater depth.

And besides, drinking tea is just an experience, not the kind of things words convey especially well, but stories are well suited to words, if an author is up to expressing it well. That's a rare skill, really, almost a lost art. We tend to be more visually oriented now, with television and movies often relying on pre-established characters and simple story-line formats, so even dialogue and plot development aren't so necessary. Related to social media a meme is easier to take in than two sentences of text, and you'd better have a good reason for someone to read two paragraphs, or else speak to a very limited audience.

So it seems that I'm implying some contradiction already, that somehow embracing narrative themes could restrict our direct experience of reality, interfere with our "Zen-like" direct perception, but at the same time saying that it's a good thing to do the same in the name of story telling. But really those are two different things. Me experiencing having a bad lunch or unusually clear traffic on the way to work doesn't require any story line. Whatever O. Henry wrote about did, but part of that was skill in sketching very limited ideas into a story. The opposition becomes really complete, doesn't it? All day I have many events and possible relations to ignore or interpret, but a short story skips almost everything on that level, or uses those ideas very efficiently, touching on very few to establish a context and push a plot forward.

To skip ahead, the trick might be setting up the cut-off then, to ignore most events as random noise that isn't especially meaningful, and at the same time be able to maintain awareness on a higher level, to keep track of some running themes or underlying contexts. This may seem to be kind of aside from the point of Buddhism but in a sense this is most of the main point, that we make every moment, every event, every read on everything as all about us, extending from desires and will into lots of relations and future possibilities. We add noise, and that takes away value, and often we're missing the real point, just being present.

Another reason I link these subjects is from my own experience in writing a journal, more than anything related to the study of Buddhism. To some extent we all experience a voice in our head--there's a really odd story about that, best to let it go to another day though--and related to writing a journal how I experienced that had changed. As I was experiencing things I'd do the arranging, living more as if I was writing out what was happening, at least on that one mental level. It was odd. I guess I still do to some very limited extent, but it had changed a lot due to writing about things on such a regular basis, every day. Instead of just drifting around a bit related to other ideas, where something might lead, something relating to something else, the story lines became more pronounced.

It's odd to say that's somehow the opposite of Buddhism, that it's an aspect of an anti-enlightened state to do even more with interpreting experience than is typical. Maybe it's really not. Again, Buddhism is about rejecting self, and desire, about suffering caused by overlaying direct experience with a layer of ideas about what we want, as opposed to what we are actually experiencing. If we always taste food and think of how some other version of food was so much better that could be an example, but really it's not even that simple. An underlying fear of death might work better as an example, some type of vague context that ties to us always wanting or not wanting something without it really directly relating to what we are doing, with this coloring immediate experience. Or in more ordinary, mundane terms maybe a constant desire to be more successful or wealthy works better, adding an extra desire and some constant lack. Adding more arrangement of ideas into stories might just be irrelevant instead, in comparison.

Or is it? I don't have so much opinion on this; it's not clear to me. As I take Buddhism--just my take, not any sort of accepted truth, of the matter--it's about rejecting desire that leads to more suffering (back wanting to be wealthy, or own specific things, etc.). It could also be about limiting mental noise, chatter that just doesn't lead anywhere in general. Or it could possibly relate to my uncle focusing on wanting to win the lottery, any type of putting desired experience outside the range of actual experience. My uncle did win a significant amount in the lottery once, not the millions that really changes things, but enough to offset some of playing it all the time. It probably just made that desire worse, but I'd never talked to him about all that, so maybe he did become a happier person instead, for having that money and achieving some degree of a life-goal.

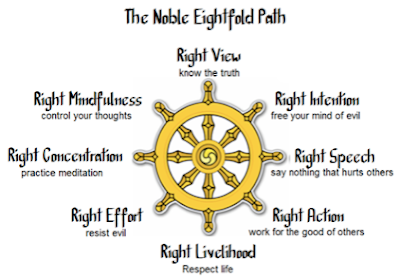

How would someone really embrace mental quiet instead? That's probably better left to another post, but I'll say a little about it. Meditation would be the obvious answer, wouldn't it, since the subject is Buddhism? I'm not so sure how that would help, but it may. I did a lot of meditating once, when I was a monk, and some well before that, experimenting. I think taken alone meditative practices wouldn't naturally do the trick but along with other elements of Buddhism maybe they could combine together to help lead to a quieter mind. So I guess I'm just endorsing the eightfold path idea.

As far as me writing a journal and that leading to sort of narrating while living, I let it go, and the mental habit dropped with it. It was really more complicated than that how it worked out, but this is about as far as I'm likely to get in the space of a few pages of text. It's almost a separate subject, but not really completely separate, but it's odd how writing about tea and just experiencing tea instead plays out (tied to the idea of blogging about tea). It can kind of throw the enjoyment off, adding a work element, but I think different people would experience that differently. Formal review forces one to identify and judge aspects, which probably wouldn't happen to the same extent just drinking a tea, unless that was part of some learned process. One might refer to the Japanese tea ceremony for reference to what Buddhism would say about just drinking tea versus a more formal experience of doing that, but per my understanding that gets quite complicated, not at all closely tied to any particular interpretation of Buddhism.

I hope that all this was clear enough, even though it didn't necessarily lead to any clear conclusions.

No comments:

Post a Comment